Prof Helena Teede, A/Prof Joanne Enticott, Dr Rhonda Garad,

When Kylea Tink, Member for North Sydney, decried the “unconstructive noise and aggression” in Australia’s Parliament this week, she wasn’t merely venting frustration. She was challenging the nation‘s political culture, a gesture that marks a turning point in the gender dynamics of Australian leadership.

This significant moment dovetails with Australia’s impressive rise in the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Report 2023. The country catapulted from a mediocre 50th in 2021 to a commendable 26th rank recently. This leap is not accidental; it results from deliberate political action to empower women.

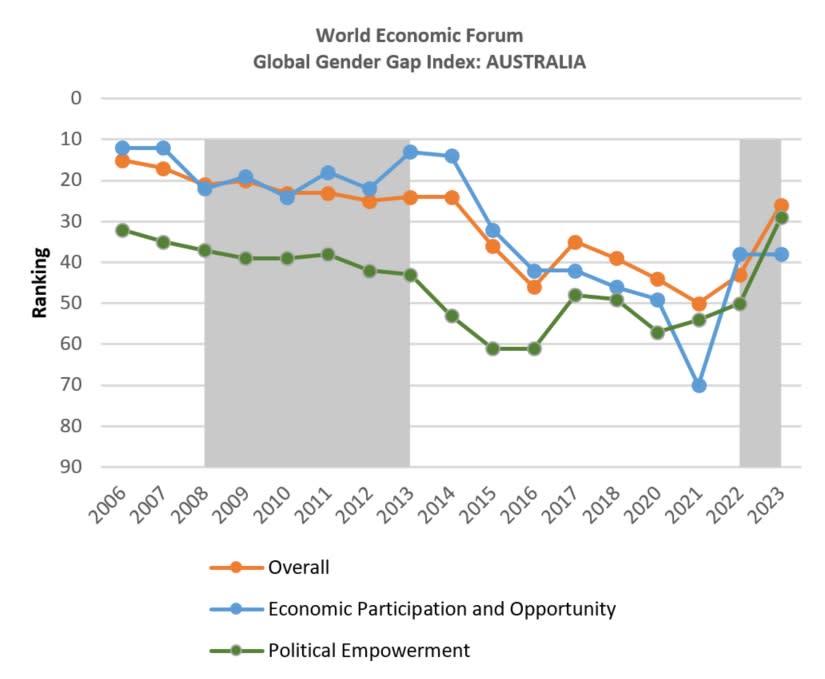

The Global Gender Gap Index annually benchmarks the state and evolution of gender parity across four key dimensions (Economic Participation and Opportunity; Political Empowerment; Educational Attainment, and Health and Survival). It’s the longest-standing index tracking the progress of numerous countries’ efforts towards closing these gaps over time since its inception in 2006.

Further progress has been made in Economic Participation and Opportunity. Australia’s rank has climbed from 70th in 2021 to 42nd. While this is a laudable achievement, there’s still much work to be done.

As of 2023, our overall global ranking stands at 26, which has improved since last year, but is still behind New Zealand’s fourth place, Rwanda’s 12th, and the UK’s 15th.

Monash University academics Professor Helena Teede and Associate Professor Joanne Enticott, from the Monash Centre for Health Research and Implementation (MCHRI), have confirmed this upward trajectory.

Their analysis (See Figure 1) of a series of World Economic Forum reports reveals a clear link between political empowerment and improved gender equity ranking. They also show how quotas, affirmative action, and other targeted measures have dramatically increased the number of women in politics.

“The gender makeup in Parliament is not just symbolic, it’s instrumental to national progress,” says Professor Teede.

The overall rise in ranking in the Gender Equity Index is largely a result of the increase in the number of women in political leadership.

Overall, women make up 45% of federal parliamentarians. While Labor and the Greens lead with the highest representation (53%) of the political parties, independents have the highest representation of women (77%).

In stark contrast, the Liberal Party and the Nationals lag significantly behind (28%).

Meanwhile, smaller parties such as CA (Centre Alliance) and JLN (Jacqui Lambie Network) show 100% female representation, but their small size has less impact.

This illustrates that while Labor and the Greens are making significant strides as a consequence of equity policies, others without these policies have a long way to go, reflecting the broader cultural and institutional challenges that still need to be addressed.

MCHRI academic and local government councillor Rhonda Garad emphasises the spillover effect of more women in political power.

“A critical mass of women in government can transform a culture, leading us from power displays to more respectful collaborative environments that benefit the nation,” she says.

All authors are at pains to point out that the imperative for change is not ideological, it’s empirical.

Take, for example, the recently-passed Workplace Gender Equality Amendment, aiming to close the gender pay gap. Starting in 2024, employers with more than 100 employees will have their gender pay gaps published.

A direct consequence of a more gender-balanced Parliament, this amendment is critical to addressing the current 13% national gender pay gap (compared to 15% in OECD countries).

The spillover of transformative leadership extends beyond politics, positively impacting the corporate, not-for-profit, and healthcare sectors.

Initiatives such as the $5 million National Advancing Women in Healthcare Leadership Program, spearheaded by Professor Teede, serve as prime examples of intentional structural reform. This program is designed to elevate women into healthcare leadership roles, with the specific aim of measurably improving outcomes for women.

The National Workplace Gender Equality Agency’s data corroborates that organisations with more women in leadership roles are more profitable and efficient.

And it’s not just about the economy. Associate Professor Enticott sums it up:

“This is not just a women’s issue, it’s societal. It impacts the entire health of the nation, both economically and socially.”

The good news is that in 2023, the world has closed about 68% of its gender gap, improving slightly from last year. At this slow pace, though, it will take 131 years to reach equality between men and women.

While no country has fully closed its gender gap, Iceland leads the pack, and New Zealand in the Asia Pacific is doing very well (largely the legacy of Jacinda Ardern’s gender reforms). Different areas such as health and education are closer to equality, but politics and jobs still have a long way to go.

Australia has made some progress, but we’re still behind countries such as New Zealand and Rwanda. If we keep moving at this rate, it will take centuries to close the gaps in politics and the workforce.

So, when leaders such as Kylea Tink call for change, they join a collective effort to dismantle the outdated strongman politics that has long stalled Australia’s progress.

She contributes to a broader momentum for the intentional, strategic empowerment of women, an approach already yielding substantial gains in economic, corporate, and healthcare sectors.

It’s well-known that the middle years for most women are a perfect storm of competing stresses, from intergenerational caring, to hot flushes and cooling libidos.

But what’s surprising is new data in our paper, led by Joanne Enticott and Graham Meadows, Mental Health in Australia: Psychological Distress Reported in Six Consecutive Cross-Sectional National Surveys From 2001 to 2018, which shows middle-aged women have gone from a place of relative mental calm, to reporting the highest level of serious mental distress.

Almost one in five women aged between 55 and 64 are reporting high distress. Over a 16-year period (2001 to 2017-18), rates of very high distress rose substantially from 3.5% to 7.2%, and high/very high distress from 12.4% to 18.7% – a rise higher than any other group.

So, what is distressing middle-aged women?

One clue is income. This dramatic rise in mental distress is closely associated with financial insecurity. A large portion of Australian women grow poorer as they move along a socially and politically engineered, gendered poverty trajectory.

“Older women are reaching retirement age in the realisation that a lifetime of lower financial opportunities has compounded into retirement years living below the poverty line.” – Emily Callander, Health Economist.

Women face a cascade of gender-specific financial assaults across their lifetime, resulting in a reverse-wealth trajectory. The assaults are so deeply entrenched that more than a third of single women will live in poverty by the age of 60.

“I have worked all my adult life, only to come to the end and find I have very little to show for it.” – Kristine, 62

We’re told that the Australian dream means the harder we work the richer we become. However, a large proportion of Australian women, despite a lifetime of hard work, will end up with meagre retirement savings and few assets, and will be at high risk of slipping quietly and invisibly into homelessness and poverty.

Conversely, men’s wealth accumulation starts early and generally builds without interruption across their working life. Starting their working lives on a higher income and moving more quickly than women to higher-income positions not only maximises their ability to purchase assets, but also boosts their superannuation saving early, which yields greater returns at retirement.

The poverty trajectory for women is the culmination of many, seemingly unconnected factors, rather than one single issue. Factors such as a persistent and pervasive pay gap across women’s working life, a tax system favouring high-earning males, and lower superannuation payments in lower-paid, insecure jobs. Add to this, time out of the workforce for parenting, and you have a slow-building but inevitable path to gendered poverty.

Women working towards poverty.

On the current trend, neither our daughters nor five generations of their offspring will live to see the gender pay gap closed. The pandemic has exacerbated gendered disadvantage by adding 36 years to reach gender pay parity (now at 136 years). Currently, women in Australia earn $255.30 less than men each week.

The gender pay gap adds up to women losing more than one million dollars over a lifetime.

Things are not improving

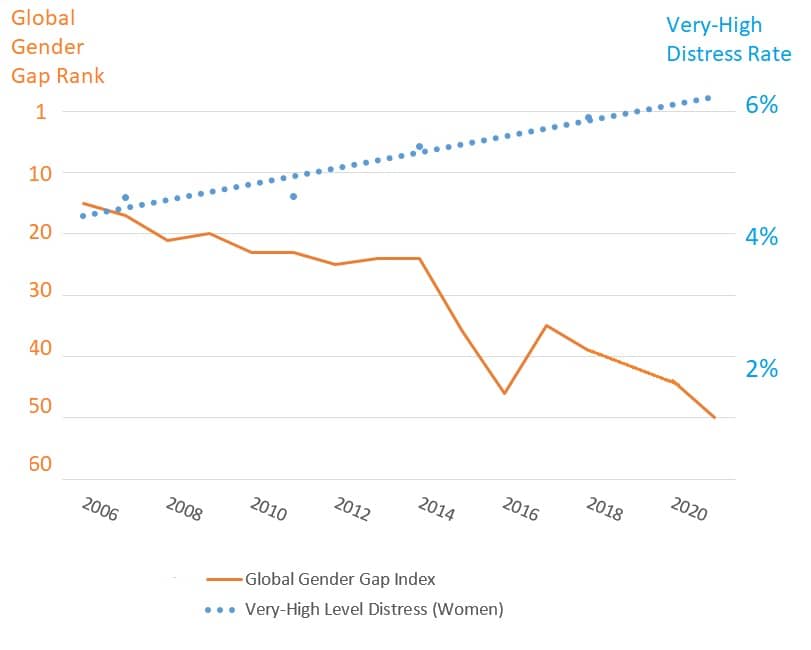

Australian women’s ranking on the Global Gender Gap Index went into freefall in 2021, dropping from 44 to 50 (behind Zimbabwe and Montenegro).  High-level mental distress rate for Australian women as measured in national health surveys. The Global Gender Gap Index is reported by the World Economic Forum. Australia’s ranking within 156 countries is shown; for example, in 2006 Australia ranked 15th, and in 2021 has dropped to 50th.

High-level mental distress rate for Australian women as measured in national health surveys. The Global Gender Gap Index is reported by the World Economic Forum. Australia’s ranking within 156 countries is shown; for example, in 2006 Australia ranked 15th, and in 2021 has dropped to 50th.

The opportunity costs of caring

Career breaks to care for children have multiple impacts on women’s wealth accumulation. There’s loss of salary while out of the workforce, and loss of superannuation accumulation, but also the opportunity costs of job promotion, connection to professional groups, moving into senior positions.

Also, women slide down the “merit” ladder during this phase, making re-entry more challenging. Consequently, they’re more likely to return to lower-paid positions.

Female-dominated industries pay less

Whilst the gender pay gap is present in all industries, a large portion of women will work in female-dominated industries (health and education) that have lower salaries on average, including their base salary and total remuneration, when compared to males.

Tax cuts for the wealthy doubly advantages men

In recent years, we’ve seen the winding back of the progressive tax system to one that rewards high-income earners. Recent changes have lowered the tax paid by the top earners (twice as many men in this group as women). Therefore, for every $1 of the tax cut that women get, men get $2. A gendered analysis shows women will receive about half the benefit compared to men, with the average annual tax cut for a man to be $1430, while for a woman at $730.

Financial impact of intimate partner violence

About one in three women from the age of 15 have experienced abuse from a current or past intimate partner.

Women’s financial health suffers within, and after leaving, an abusive relationship, with about one in five women moving into financial hardship.

Women are twice as likely to experience financial abuse, particularly where disability is present. Economic abuse is a form of intimate partner violence, and can involve economic control, economic exploitation, and employment sabotage. It represents a significant barrier to women leaving violent relationships. Women aged 30 to 59 reported the highest prevalence of economic abuse overall.

And, for the women who do leave an abusive relationship, they’re more likely to receive a smaller share of the couple’s wealth while having financial responsibility for children, and may suffer abuse of the legal system by a partner who prolongs the legal process of wealth-splitting.

Women’s risk of all forms of intimate partner abuse has substantially increased during the pandemic – women reported either first-time abuse, or exacerbation of abuse, within their intimate relationship during this time.

Single status and poverty

The wealth of women is still very much dependent on their partner’s income. Single status in older women is synonymous with financial disadvantage.

Single Australian women over 60 are the most likely household to live in poverty, earning less than $30,000 a year.

Divorce accelerating poverty for women

The impact of divorce on men generally causes short-term interruption to wellbeing, while women chronically spiral into disproportionate household income losses and increased risk of poverty, homelessness and single parenting.

The number of older homeless women in Australia increased by more than 30% between 2011 and 2016 to nearly 7000, the fastest rate compared to any other group.

Retiring in poverty

On average, women retire with about one-third less superannuation than men, with the gap being anywhere between 22% and 35%. The median superannuation balance for men aged 60-64 years is $204,107 whereas for women in the same age group it’s $146,900, a gap of 28%. For the pre-retirement years of 55-59, the gender gap is 33%, and in the peak earning years of 45-49, the gender gap is 35%.

“I am in my early 60s and I know I can never retire. When I stop working, I will stop having a roof over my head and food on the table.” – Gillian, 63.

Bi-directional relationship between wealth and mental health

The relationship between psychological distress and poverty works both ways. Those living in poverty can develop psychological distress, while those with psychological distress are at higher risk of falling into income poverty.

Women are over-represented in high levels of psychological distress (63%), and are more likely to live in poverty (20%, rising to 33% at age 60).

Enough is enough

The results of our study, showing the rise in serious mental distress in older women, should serve as yet another red flag to leaders and policymakers.

Just over a year ago, more than 110,000 people took to the streets around Australia and said enough was enough.

Enough of silencing the voices of women on abuse, enough of the lack of equal representation, and enough of a system that culminates in a large portion of women living in hard-earned poverty.

The reverse-wealth trajectory women experience is indefensible and must be addressed as a matter of urgency. We need coherent policies from government and business leaders that deliver gender equality in wealth creation.

Is it time for a women’s health institute?

Professor Helena Teede, Director of the Monash Centre for Research Health and Implementation (MCHRI), says we can no longer fail to recognise and address the fact that inequity by gender is a major challenge in this country with key health and wellbeing impacts, especially for women.

“The reverse-wealth trajectory women experience is indefensible, accelerating, and must be addressed urgently. We are seeking bipartisan support for a national institute to drive evidence-based, women-centric policies from government and business leaders that deliver gender equality in wealth creation to improve subsequent health and wellbeing for, and with, Australian women,” Professor Teede said.

Monash University is working to establish a national institute to support women of all ages. It will work across the social determinants of health with a strong focus on financial insecurity and equity to optimise health and wellbeing.

This article was first published on Monash Lens. Read the original article